Since the Premier League was founded in 1992, it has consistently marketed itself as the best and most competitive league in the world. While this likely still rings true, the vast swathes of money that have poured into English football over the last 30 years have created an increasingly predictable and unequal league compared to the previous Football League First Division.

The broadcast distribution model, which has facilitated the league’s growth, has led to significant income disparities for the top teams. For the 2021-22 season, this gave winners Manchester City £146.29 million, while bottom-placed Norwich received £93.79 million.

This has helped the so-called “big 6” to consistently finish towards the top of the table, while almost removing them from the danger of relegation. This was certainly not the case before the creation of the Premier League.

For the modern football fan in the summer of 2015, Leicester City being champions the following year was almost incomprehensible. The chances of a team battling relegation one season and winning the title the next season were minute.

However, during the period between 1959 and 1987, this was less of a foreign concept to the English football fan.

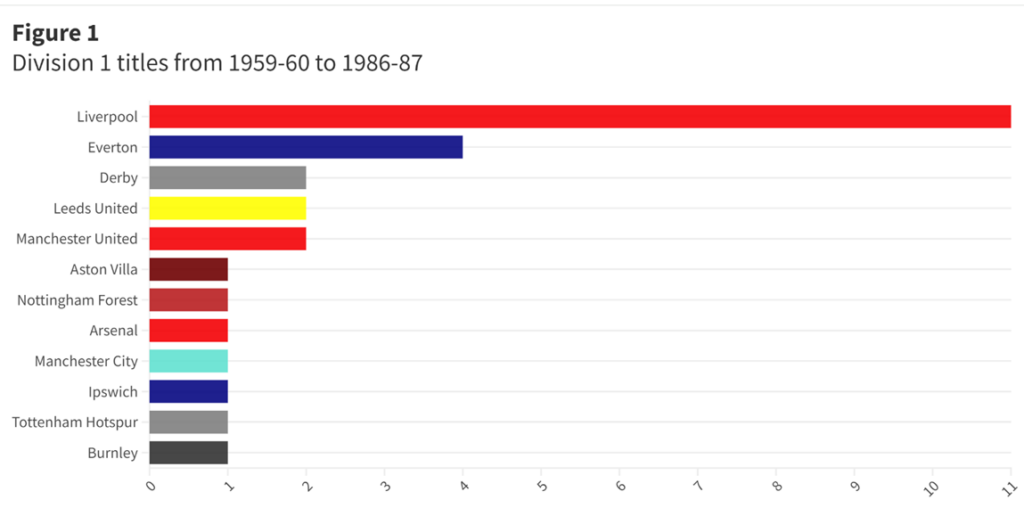

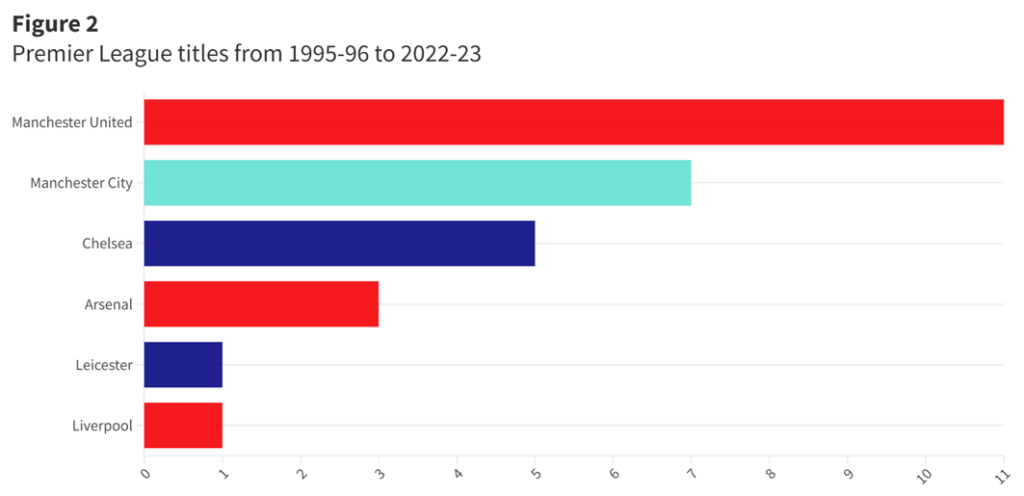

Amongst the first period, 12 different teams won the league, including five instances where a team ‘did a Leicester’. That means a team that finished from a position of 9th or below the previous season, won the league the next season.

Among the five teams, there were also two who had won it directly after being promoted.

In the second period, there were six different teams that won the league and just two who had ‘done a Leicester’.

Leicester, obviously, who had finished 14th prior to their title, and Chelsea, who won the league in 2016-2017 after a dysfunctional year previously, which saw Jose Mourinho leave mid-season.

However, Chelsea’s return to the top was not comparable to Leicester’s league win.

The aforementioned broadcast distribution model had already created a group of financially elite clubs. It was never a question of if Chelsea would return to the top, it was a question of when.

Before the creation of the Premier League, finances still played a part in a team’s ability to sustain themselves, but not to the level of today. Managers, academy prospects, and transfer policy all held a larger stake. It was a system based on merit more than wealth. Where merit is fluid, the wealth we see today is not.

Great managers could leave or retire, new tactical ideas could trump old ones, and a great crop of players could come through an academy. The riches at the top of the game now essentially inhibit these changes from having a pronounced impact on the status quo.

Take Brighton and Manchester United in the modern Premier League. Brighton has an academy and transfer policy that work in harmony with the manager and team on the pitch. Regarded as one of the most polished club models in the league, they have finished in the top half in the past two seasons, despite having the second-lowest wage bill in the division.

Manchester United are the antithesis of everything Brighton does. They’re a club made up of dysfunctional parts struggling to work in harmony. Yet Manchester United have finished above Brighton every year since Brighton returned to the Premier League in 2017. A huge contributor to that is that their yearly revenue is three times that of Brighton.

The addition of world-class managers to the equation has exacerbated the problem, despite the entertainment that they have provided. The blend of Pep Guardiola’s tactical ingenuity mixed with the financial might of the City Football Group has seen an increase in the number of points needed to win the league.

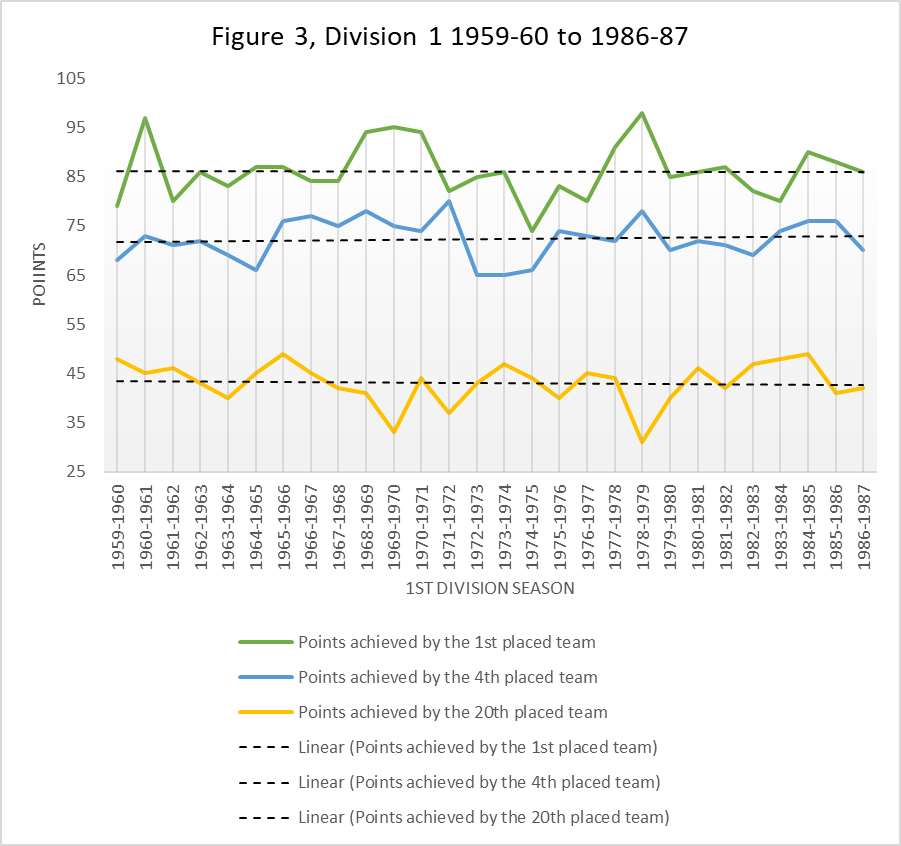

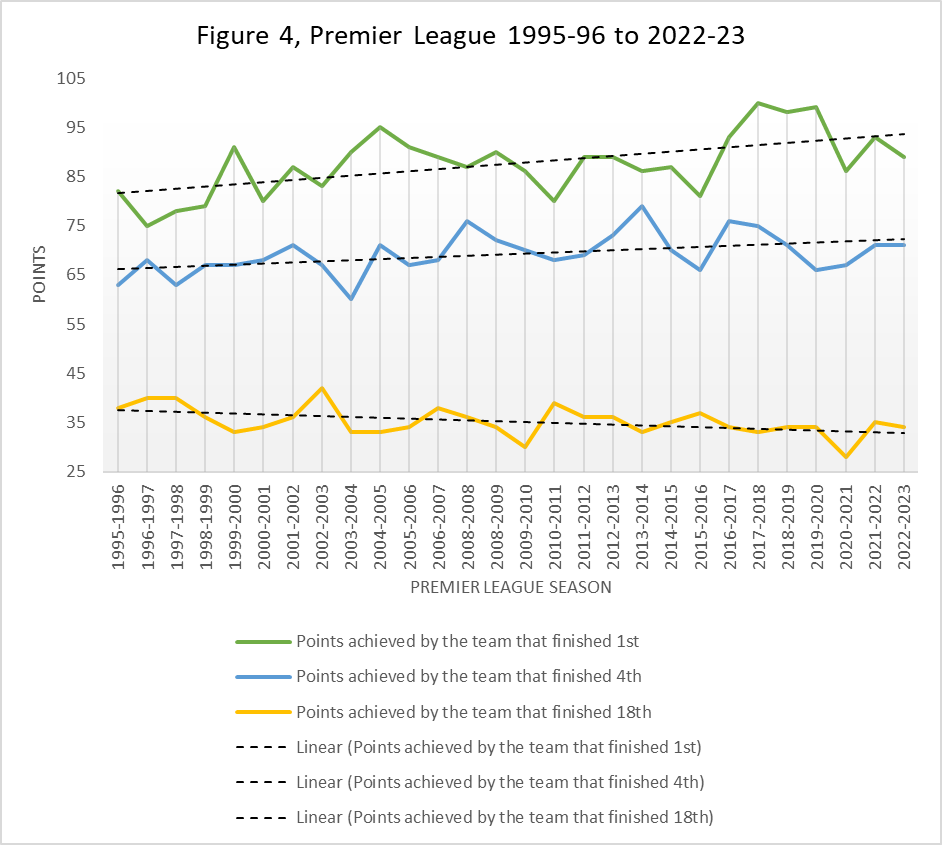

Figures 3 and 4 looked at the same period as Figures 1 and 2 but show the number of points that teams required to finish first, fourth, and 20th for the 1959-1987 era and first, fourth, and 18th for the 1995-2023 era.

Fourth was chosen since, from 2001-2002, this guaranteed a place in the Champions League qualification round, while 18th and 20th were chosen to see the standard of the relegation or lower-placed teams.

There were 20 teams in the division during the Figure 3 period and 22 during the Figure 4 period.

The first period shows a flat correlation as teams were unable to improve at a significant rate compared to other sides.

However, the later period shows the league winners’ points total has a huge upwards trajectory. The teams that win receive the larger portion of the broadcast revenue, giving them a greater income and more expendable money. Coupled with financial fair play rules, it’s a difficult cycle to break.

UEFA ruling states that teams can report losses of £60 million over a 3-year period, so clubs that earn more money can spend more.

The adverse effects of this system are seen in the relegation data set. As exactly how the cycle is positive at the top, it is negative at the bottom. The standard of the top teams has made it harder for the lower-placed teams to pick up points, creating a system which grows more unequal by the year.

With the Premier League recently agreeing on a new record £6.7 billion TV rights deal, it appears that these problems will continue into the foreseeable future. While the league still retains enough unpredictability to keep fans engaged, one wonders whether we’re headed to a point where some casual fans may begin to lose interest. The Bundesliga has seen viewing figures decline in recent years in part due to Bayern Munich’s dominance. Is the Premier League heading this way as well?